حسام الدین شفیعیان

وبلاگ رسمی و شخصی حسام الدین شفیعیانحسام الدین شفیعیان

وبلاگ رسمی و شخصی حسام الدین شفیعیانیهودا اسخریوطی

Readers: The Gospel of Nicodemus: Judas went home to make a noose of rope, in order

to hang himself, and he found his wife sitting down and roasting a cock over a charcoal

fire prior to eating it.

He said to her, “Get up, wife, and find a rope for me, because I want to hang

myself, as I deserve.” But his wife said to him, “Why are you saying these sorts of

things?” Judas said to her, “In truth, you should know that I have handed my teacher

Jesus over in a wicked way to the evildoers, so that Pilate might execute him. But he will

rise again on the third day – and woe to us!” His wife said to him, “Don’t speak or think

like that. For it is just as possible for this cock roasting over the charcoal fire to crow as

for Jesus to rise again, as you are saying.”

And immediately, as she finished speaking, that cock spread its wings and crowed

three times. Then Judas was convinced even more, and immediately he made the noose of

rope and hanged himself.

Although lost for centuries, the Gospel of Judas was known to have existed because it was mentioned by St. Irenaeus of Lyon, who condemned it as a fiction in AD 180. However, a Coptic translation (c. 300) of the original Greek text was discovered in a codex found in Egypt in the 1970s. In 1978 the codex was acquired by an Egyptian antiquities dealer, who placed it in a safe-deposit box in New York state, U.S., after his attempts to sell it failed. It remained there until 2000, when it was purchased by the Swiss-based Maecenas Foundation for Ancient Art. The reconstruction of the folios and a study of their contents were commissioned, and the text of the gospel and a translation were made public in 2006. Along with the Gospel of Judas, the codex contains the pseudepigraphal (noncanonical and unauthentic) First Apocalypse of James, a letter of the apostle Peter, and a section of a badly fragmented work provisionally identified as the Book of Allogenes or Book of the Stranger, a Gnostic text that was also among the codices found at Najʿ Hammadi in 1945.

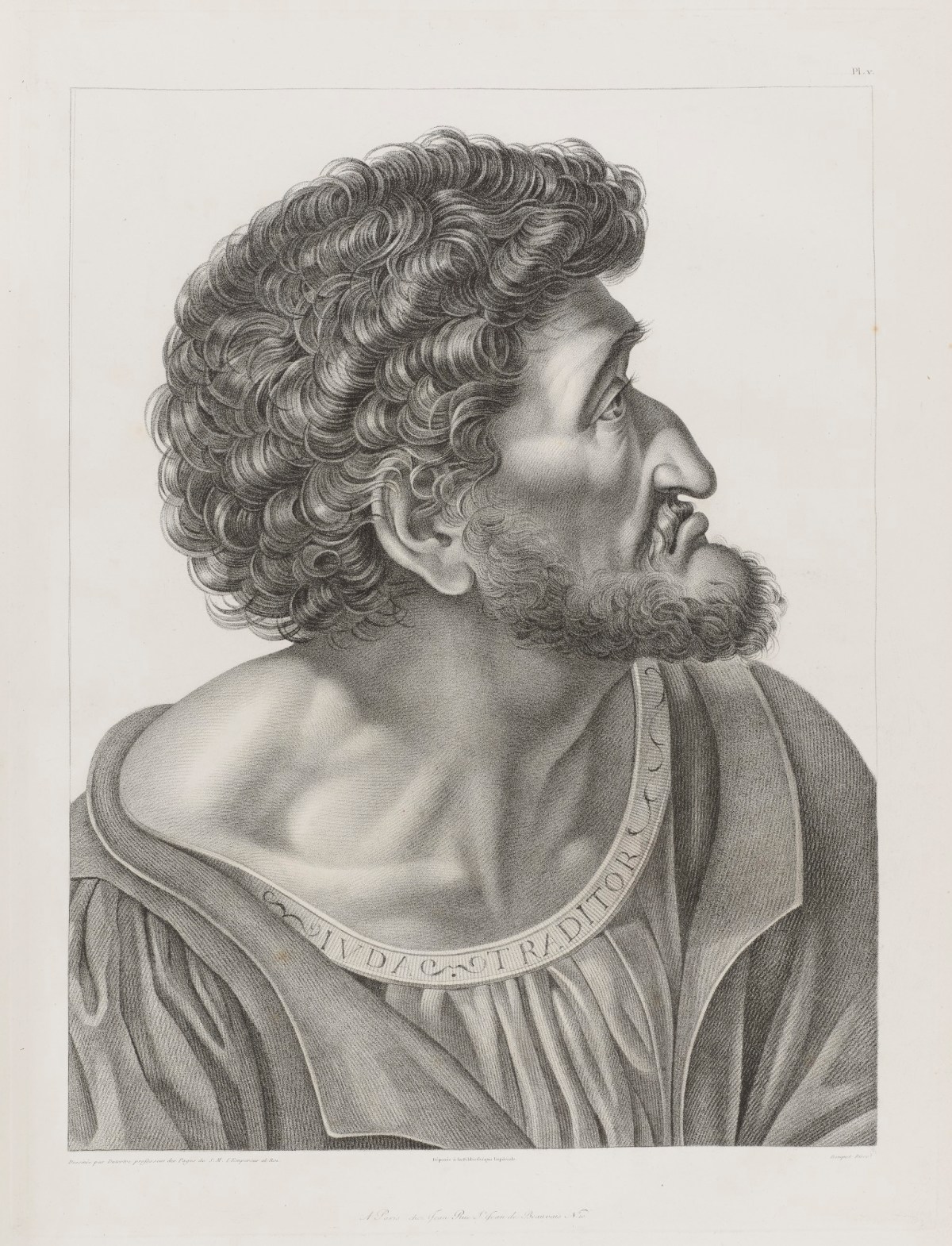

Judas Iscariot

Judas Iscariot, (died c. AD 30), one of the Twelve Apostles, notorious for betraying Jesus. Judas’ surname is more probably a corruption of the Latin sicarius (“murderer” or “assassin”) than an indication of family origin, suggesting that he would have belonged to the Sicarii, the most radical Jewish group, some of whom were terrorists. Other than his apostleship, his betrayal, and his death, little else is revealed about Judas in the Gospels. Always the last on the list of the Apostles, he was their treasurer. John 12:6 introduces Judas’ thievery by saying, “. . . as he had the money box he used to take what was put into it.”